Pursuing Hydrography with Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Airlie Pickett

This blog was written by Brandon Rodriguez, a science communication fellow onboard E/V Nautilus.

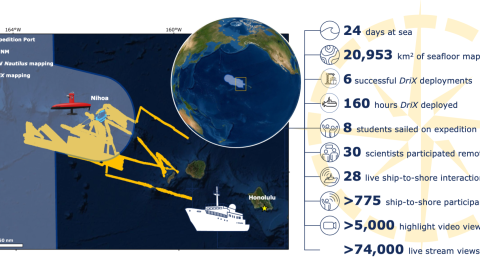

One of the keys to successful E/V Nautilus expeditions is the wide breadth of skills and backgrounds that come together. The team aboard the Luʻuaeaahikiikawawāapalaoa cruise, an expedition to test new technologies and map the seafloor in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, is no exception. This work represents new partnerships led by Ocean Exploration Trust (OET), partnering with NOAA and Ocean Exploration Cooperative Institute partners like the University of New Hampshire (UNH).

One such scientist aboard the ship, NOAA Corps Lieutenant (junior grade) Airlie Pickett, demonstrates to what degree every team member contributes to the big picture, bringing a rich background and knowledge to make the team greater than the sum of its parts.

NOAA is a branch of the Department of Commerce that includes the National Weather Service and multiple other line offices with scientific missions. Within this government office, professional officers on NOAA vessels and aircraft collect scientific data about the planet for internal and external stakeholders, often directly for the people of the United States. They work with data in many forms, including collecting weather data from planes and satellites, using ships and small boats to gather bathymetric information, analyzing fisheries surveys, and more. The NOAA Commissioned Officers Corps is a group of highly mobile, flexible uniformed officers whose mission is to support the federal agency in operational and scientific roles.

Pickett is one of two NOAA Corps Officers aboard the Luʻuaeaahikiikawawāapalaoa expedition, representing the first foray into the collaboration between the Corps and OET's at-sea operations on E/V Nautilus. She is currently working on her Master of Science at the University of New Hampshire, studying hydrography. She will finish her degree in 2024 and will likely be assigned to one of NOAA's hydrographic ships as an operations officer, a role that includes determining how the ship can meet its scientific goals.

Her undergraduate career is of particular note. Pickett enrolled at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington in 2010 with aspirations of being a marine biologist but soon found her passion lay elsewhere. She was a history major three years later and settled on physics- specifically, physical oceanography.

That led her to the field of hydrography, which can be niche yet draws upon a critical skill set for understanding the ocean through map making. Hydrography is needed on all mapping expeditions like those conducted by Nautilus.

"I always liked being operational and scientific at the same time - hydrography allows for a hands-on and decisions-based role aboard. The NOAA Corps really facilitated a career doing both, which has given me a very nuanced perspective on the field," said Pickett.

"This was a role that began with the original goal of safety in navigation but has expanded to purposes well beyond that, including habitat mapping for marine sanctuaries, energy exploration, geophysical research, and a multitude of other applications."

A core tool used on seafloor mapping expeditions aboard Nautilus is the acoustic systems that characterize the seafloor through collecting bathymetric data. This is a complicated and complex process that, through her studies and professional experience, Pickett has built expertise through. She shared some of the elements of the work she finds most fascinating.

In making a map of a new ocean area, "the first question you have to ask is how do you know exactly where your vessel is? Horizontally, this process is (relatively) simple due to modern technology," explained Pickett.

"There are usually at least four satellites in space on your horizon that can pinpoint where you are in the horizontal plane, but knowing where you are in the vertical direction relative to the center of the Earth? That can be more difficult".

That's because sea level isn't level, and at any moment while collecting data, ships are subject to tides, waves, winds, and even the asymmetric nature of the Earth.

Traditionally, hydrographers used straightforward reference tools such as mean lower low water (MLLW). This vertical reference uses the measured average water level at lower low tide as a baseline. However, this resulted in regional, nautical charts that could not be easily stitched together, as tides vary geographically, and the stations are not always as prevalent as they need to be to evaluate the water levels in an area accurately.

Pickett elaborated that in modern hydrography, "we use a simplified model of the Earth, called the ellipsoid, to reference our measurements against." The ellipsoid is a smoothed surface that approximates the shape of Earth. This surface gives us a consistent reference frame for measurements that can be used worldwide. However, modeling and calibration aren't the only parts of the job, as Pickett's skills draw upon her physics background in instrumentation, namely in echosounding.

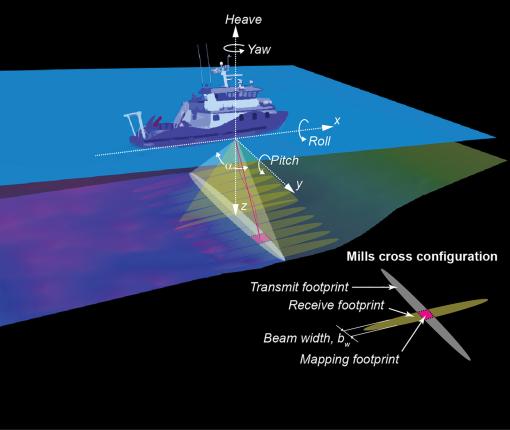

In a mapping sonar, the sound is transmitted from a submerged echosounder and is usually detected by a co-located receiver. That sound isn't only going straight down — it also fans out to either side of the vessel at angles. As the sound travels, it experiences refraction of sound fan "beams" due to changes in the sound speed in the water column, which is influenced by factors like salinity levels and temperature. This refraction change must be measured and accounted for to accurately reconstruct the data from each beam on the seafloor. These measurements are done by taking sound speed casts and then tracing the path the sound takes as it travels down to the seafloor and back up to the ship.

Collecting data is complicated by the fact that while sounding is occurring, the vessel is moving, meaning that those angles aren't constant with respect to the surface of the water. Thus, one must characterize the vessel's movement, typically done with an inertial measurement unit (IMU) that measures the vessel's pitch, roll, and heave. Combined with the topside positioning discussed above, hydrographers can accurately locate each ping on the seafloor.

Sailing on Nautilus as a NOAA Corps officer, Pickett has benefitted from training and seeing commonalities between OET and NOAA operations.

"Nautilus has been a great experience broadening my overall vision as an officer and scientist. Much of my previous experience has been NOAA-centric," she said. "Part of being a well-rounded officer is [having] knowledge of the missions within the agency [NOAA], as well as our partnerships with the broader scientific community. My time aboard Nautilus has directly exposed me to these collaborations. As I develop as an officer and interact more with the community outside of NOAA, this experience will be critical in fostering connections and informing my actions and decisions."

In her capacity as a UNH graduate student, Pickett adds that she has spent the majority of the past year in the classroom learning about the science of ocean mapping. This cruise, she said, also gave her hands-on "operational paring" to her learning.

When asked what misconceptions she wanted to address about hydrography, Pickett said that she's often surprised by how little of the history of the Corps is common knowledge, considering the field's rich history, even long before the formation of NOAA.

There is such "a lack of awareness of the history and scope of the field. NOAA's Coast Survey, tasked with charting our Nation's coasts, is the oldest scientific organization in the United States, originally put into place by Thomas Jefferson, and is the foundational agency from which NOAA was born," said Pickett. "It's incredible to be part of so much history and simultaneously the future of exploration."

A successful expedition relies on the combined and diverse backgrounds in numerous disciplines. Pickett represents how the Nautilus Corps of Exploration is strengthened by a team bringing complementary skills from varying institutions to further the scientific goals of ocean exploration safely and sustainably. For students interested in following in her footsteps, Pickett has some advice.

"My tip for young people as they get to college: Nobody really knows what they're doing at that age; just jump in and give things a shot! It took a while for me to find my footing, but I knew it when I got there," she said.

"With physics, I first fell in love with the people, then started to appreciate the role it had always played in my life as a surfer and a diver. It brought real-world applications paired with the scientific foundation to accomplish them."

To learn more about people who make deep ocean exploration expeditions possible or the roles and opportunities for aspiring explorers, be sure to check out the Nautilus Live and NOAA Corps websites.

Luʻuaeaahikiikawawāapalaoa: Dual-Technology Seafloor Mapping

This expedition focuses on high-resolution mapping areas of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM) currently lacking data using ship-based mapping surveys in deep waters as well as deploying the uncrewed surface vessel DriX for nearshore mapping.