The Special People That Work on Ships

This blog was written by Andrea Vale, Junior Video Engineer

On one of my first days here on the E/V Nautilus, one of my shipmates said to me, “Remember, normal people don’t work on ships.” It seems to me it wouldn’t be possible to do this work any other way. By nature, it requires people who embrace a bizarre and challenging existence, doing our best to rewire our bodies to work against the way they always have.

Here, we sleep in small one-to-two hour bursts throughout a 24-hour work day. We set alarms for an 11:30 p.m. wakeup, make a midnight coffee to start the day, and ultimately end our shifts in time for an 8 a.m. bedtime. We no longer remember what it feels like to not be slightly in motion at all times, with the boat drifting and lilting even when we’re moored at a research site. Time speeds up then seizes, slows and morphs into one prolonged, milky state of being. There is no such thing as ‘day’ or ‘night’ anymore — only an uncontained Jell-O we’re cocooned in.

There are laws that take on grave importance here. Don’t sit in the captain’s seat in the mess hall. Sour patch kids are fantastic for seasickness. Always ask what people’s tattoos mean. I’ve acquired a whole new vocabulary: muster. SITREP. Bowlin. Shakedown. My first day, I sat down in the mess for lunch just in time to catch a shipmate recall, “And there we were in the open ocean with no radio, on a raft filled with bags of cement…”

I’ve somehow become intimately close with 47 strangers in a matter of days. These people are my coworkers, roommates, seasickness caretakers, rummy-competitors, and midnight confessors, all at once. We ask each other where we’re from, but the names of towns — Dingle, San Diego, Sinaloa, Asheville, Narragansett — feel like distant memories more than real places.

I’ve covered ocean research as a writer, photographer, and videographer, searching for the smallest details in the world’s most vast canvas, the sea. But as much as I love holding a magnifying glass to the ocean, my ability to do so has always been limited. I couldn’t capture what we were all there to explore: under the surface itself.

That’s why I was so elated to be hired on as a junior video engineer and have the opportunity to learn the Nautilus’ unique video system that allows us to survey, in real time, the ocean floor.

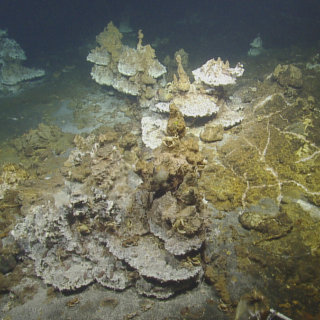

There's a bit of a catch: unlike a typical Nautilus expedition, E Mamana Ou Gataifale I NA164 — our leg here in American Samoa — won’t involve ROV Hercules diving and surveying the deep sea. Instead, we’re deploying and recovering a series of specialized instruments — the DAP Lander, the Mesobot, and DriX — to map and explore the dynamic habitats surrounding the Vailulu’u Seamount.

But one of my favorite things about video work and expedition work alike is that inevitable changes to plans are almost always opportunities for growth. This leg is totally unique, and gives me the chance to do more than the usual focus-pulling that would dominate my duties for an ROV-heavy dive. I maintain and operate a suite of cameras across the bow, starboard, amid, and around the ship; manipulate the live stream satellites; test out intercom systems; and have many other duties.

I have the midnight to 8 a.m. shift. There’s something riveting about being one of the only few awake on the ship, peering into the glow of a monitor at 3 a.m. Without sound, two of our scientists wrestle with a long, harpoon-like hook, trying to spear the blinking red light of Mesobot as it sloshes around in the waves. The control van is wallpapered with screens full of flickering lights and lines sputtering on graphs, and knowing what they’re indicating — in real time, the comings and goings of the deep sea — feels nothing less than a huge privilege.

My longtime mentor, our communications lead Marley Parker, said to me on the first day at sea, “You deserve to be here.” I’m still working on internalizing that. For me, the hardest part of working on the Nautilus isn’t the complex video systems, erratic 24-hour working schedules, or constantly-shifting plans. Those are all things anyone can get used to with enough time, and if anything I’ve found the constant novelty enthralling. Instead, I’ve found the biggest challenge to be simply accepting that amongst research so groundbreaking, and an institution so impactful, that I could also be playing a valuable role. The lead video engineer, Amber Flynn, is talented, understanding, and gracious. Under her guidance, making a mistake or not knowing what to do at the video engineering station isn’t a cause for stress; it’s a learning opportunity.

I’d wager that everyone on board possesses more than a few unique quirks, and that it’s precisely these imperfections and oddities that allow us to tackle this strange work. The magic is the natural state of the deep sea that we’re working to uncover; that’s what we should be humbled by. We’re not savants or wunderkinds — although some of the more famous scientists on board might be — we simply have that intangible weirdness that makes us want to be here. Once we are, it’s the inevitable pitfalls and challenges we grapple with along the way that prove we’re up for the job.

E Mamana Ou Gataifale I - American Samoa

Over the last three years, the Ocean Exploration Cooperative Institute has been advancing the integration of multiple exploration technologies aboard E/V Nautilus, and this year, we bring these new capacities to American Samoa.