The Gifts of Scientific Learning and Cultural Exchange at Sea

The chance to sail on an oceanographic vessel is a precious opportunity for the simple fact that it opens a doorway to that 70-or so percent of our planet that we humans are rarely privy to experiencing. Step on any long-haul research ship and you are almost guaranteed at some point to experience the startling realization that thousands of meters stand between you and the nearest underlying seafloor. It’s a humbling sensation to be reminded of how small we are. Somewhat analogous to the experience of astronauts flying in orbit miles above the Earth, you get the sense that not much stands between you and a vast unknown realm.

Despite this sobering reality, many of us readily jump at the chance to go to sea in the name of science. To understand our ocean is to love it because in discerning its inner workings, we can better inform our own actions and responsibilities as a resource-consuming species. This is at the heart of scientific research. However, what we don’t speak about as often is the way oceanographic vessels also serve as platforms for cultural exchange, an outcome I would argue is equally as valuable as our scientific takeaways. By bringing together people of different cultural backgrounds, oceanographic vessels create a melting pot of mindsets that allow us to transform the scientific method in an ever-evolving way.

As a graduate student in marine science, my experience with seafloor mapping technologies has given me opportunities to sail with institutions across the US and internationally. Over the course of these cruises, I have cherished the chance to get to know people from all different walks of life as they teach me new ways of understanding our world. As a Colombian-American, queer woman, I strive to bring my own flavor of color and open-mindedness to the work I do. Sailing with people from Europe, Asia, South America, the Pacific Islands, and different parts of North America, I have learned about many wonderful cultures and traditions.

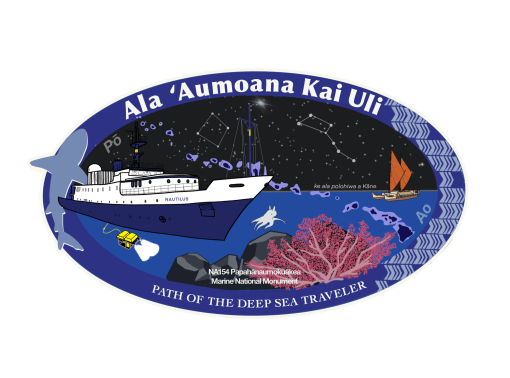

On some occasions, holidays and special events allowed me to experience them firsthand. Examples include watching the men’s soccer World Cup Final from the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean with my Argentinian and French shipmates as they cheered on their teams in the nail-biting finale! Or, experiencing a modified, shipboard German Christmas market complete with mulled wine and a chorus of O Tannenbaum in the wet lab of the German research vessel Polarstern. But perhaps, one of my most treasured experiences of cultural exchange at sea was on Ocean Exploration Trust’s Ala ʻAumoana Kai Uli expedition into Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in 2023.

The expedition was part of a collaboration since 2020, where Ocean Exploration Trust has been working to build an equitable and ethical relationship with members of the Papahānaumokuākea Native Hawaiian Cultural Working Group and NOAA Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument staff to appropriately weave Hawaiian culture into deep-sea exploration expeditions conducted in Hawaiʻi and across Moananuiākea (the Pacific Ocean). Cultivating trust and pilina (relationships) is the foundation that led to co-developing expeditions that honor KānakaʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiian) knowledge through equally valuing both Indigenous knowledge systems and Western Science. This has resulted in work to change deep-sea exploration approaches that set the tone for transforming ocean science. These approaches focus on building a culturally-grounded pilina with the deep ocean, increasing participation and self-representation of Indigenous and local community members connected to the ocean, and providing opportunities for ʻŌiwi across a diverse range of science, technology, engineering, math, and maritime careers to participate on expeditions.

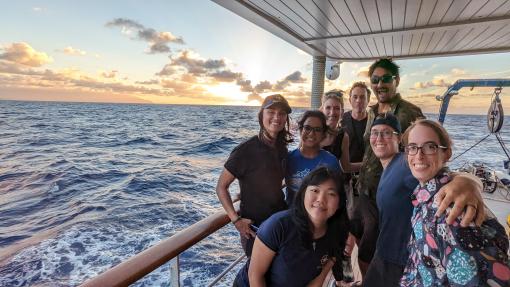

As part of Ala ‘Aumoana Kai Uli’s technical team, one of my favorite memories remains from the evening when we wrapped our incredible journey with a celebration on the back deck of E/V Nautilus. As the sun set, we sailed blissfully through the rolling blue waves north of Kaua’i and watched with wonder as the spectacular silhouette of the Nāpali Coast passed before us. After four weeks of long days filled with back-to-back ROV dives and one after the other newsworthy encounters, we finally relaxed with only a few hours remaining and basked in the satisfaction of having accomplished so many incredible things. Our encounters with dumbo octopuses and the aircraft carriers sunk during the Battle of Midway still lingered fresh on our minds and left us in a state of grateful incredulity. And as one of our Hawaiian shipmates pointed out, it was almost unreal how kindly Kanaloa – the traditional Hawaiian god of the sea – had treated us with the beautiful sea states we had the entire trip.

As we all stood together, bouncing through playlists, unwinding and preparing to return home, in a moment that seemed to tap into the collective gratitude we were all feeling, our leader in Hawaiian protocol and guest educator, Malia Kapuaonālani Evans, broke out into a spontaneous hula. Without missing a beat, our Hawaiian cultural liaison, Mahina Cavalieri jumped in and joined Malia. Immediately we turned our gazes to watch as they swayed and gestured in unison embodying the beauty of the sacred art form. Watching as they joyously danced their hula, it was impossible not to smile and feel connected to something bigger.

This ‘something bigger’ encompassed many things, among them a renewed relationship with the ocean and its inhabitants, a relationship nurtured and guided by our Kānaka 'Ōiwi crewmates. Getting to know the ocean as a being, Kanaloa, rather than an inanimate water mass as I was taught to understand it, was a learning opportunity that added great value to my work - both as a navigator and mapper on E/V Nautilus and as a professional now working in the field of ocean mapping. While I’ve always had a deep love and respect for the ocean, witnessing the added layer of familial bond that my Kānaka 'Ōiwi crewmates brought to this relationship - with Kanaloa - elevated my own sense of urgency to protect our marine realm and challenged me to expand my notions of what stewardship means.

Throughout Ala ʻAumoana Kai Uli, our Kānaka 'Ōiwi shipmates reinforced many important lessons. While we were there to execute an exploratory mission driven by questions of science and history, we were taught that to do so came with a responsibility. As a scientist trained in Western scientific traditions, I was taught to view the world through an ostensibly objective and quantifiable lens. But what they reminded us was that we must do so while also honoring the sanctity of the beings we observe and the places we observe them from. This practice is too often forgotten in Western science approaches.

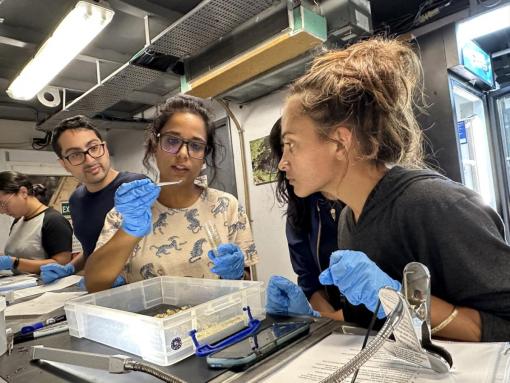

Throughout the expedition, there were moments that reminded me of the historical power dynamics, and at times remaining distance, between Western scientific and Indigenous cultural knowledge and practice. As we read species names off a list of ‘target specimens’ I couldn’t help but wonder if the scientists ashore asking for their collection would be so quick to take them from their homes had they been looking at them face-to-face and in such close proximity as I was. Despite sharing in the curiosity of these magnificent creatures, I also wondered how our presence was felt by them. We long to see and understand our deep-sea neighbors, but to what length do we satisfy our own curiosities? Is there a place for extractive sampling, especially when exploring as guests in communities’ sacred spaces? These were the kinds of questions that hung heavy in the control van and continue to deserve consideration in future science studies. While uncomfortable for some, this is the weight of our responsibility as people with the privilege of visiting and interacting with this realm.

My time on Ala ‘Aumoana Kai Uli was a brief moment in the grand scheme of time that Ocean Exploration Trust has put into building relationships with its KānakaʻŌiwi and Pacific Island partners. My experience as a newcomer came with moments of discomfort as I became familiar with the nuanced and challenging work these groups have worked collaboratively on for years. While it was, at times, easier to give into the frustration of a failed specimen collection or a cultural misunderstanding, I see more clearly now that this is part of the process. To achieve unity in our goal of exploring the deep sea in an ethical and equitable way we must work through our differences and not give up when the challenges feel like too much. Both Western Science and Indigenous knowledge systems have so much to offer us in our journey to explore the ocean. If we are able to merge them in a way that harnesses the best of both, we have the potential to achieve great things.

The mission patch is one I designed in collaboration with my Kanaka ʻŌiwi crewmates.

E/V Nautilus is an incredibly powerful platform for ocean discovery and education. It reaches audiences around the entire world and brings the forefront of exploration to anyone who has access to the internet. With this power, comes the responsibility to impart the lessons with our audiences that we were taught by our Indigenous partners. While the path that has led to now is not a perfect one, the goal is to strive for a balance of respect and wonder while we achieve the scientific goals of our expeditions. As we uncover the answers that give us an empirical understanding of our planet, we must also strive to break the bounds that limit our objective thinking. Can we instead expand our minds to come up with creative and less invasive solutions to collect the data we need? If we are smart enough to evolve as far as we have technologically, then surely we can apply that intelligence mindfully and responsibly.

For my part, I am incredibly proud to have sailed as part of Ala ʻAumoana Kai Uli. I do not glorify our work on a pedestal of perfection, but I embrace the lessons I took away from the experience and the Indigenous knowledge that was graciously imparted by my Kānaka 'Ōiwi colleagues. I learned so much from the beautiful diversity of peers that I got to work with over the 27 days we had together. We came from a wide span of backgrounds - scientists, teachers, historians, artists, Lumbee, CHamoru, Indian, Palauan, American, African American, Asian American, Latin American, Native Hawaiian, LGBTQ+, neurodivergent, and more.

We brought together different perspectives and philosophies and joined forces to shed light on the magnificent deep-sea habitats and archeological sites that lie in the depths of Papahānaumokuākea. My experiences with this team made me both a better scientist and a better person. As I move forward in my career, I am reminded that the world around me is interconnected in ways that are not possible to describe by an exclusively Western scientific lens. Our Indigenous peers remind us that there is a sacredness in everything around us, and we must care for our world as if it were our kin.

In conclusion…as my own way of saying thank you to my Hawaiian shipmates that final day on Nautilus, I offered in exchange my own expression of joy, as they had given me theirs. As the daughter of a Colombian family, I was taught from a young age the fast-paced steps of merengue and salsa. What began as a difficult tarea, or homework, mirroring the steps of my father in a rigid downward-facing focus, is now something that I indulge in with nostalgic joy when the opportunity presents itself and the music is right.

This Ti leaf lei was made for the journey into Papahānaumokuākea by our Kanaka ʻŌiwi crewmates.

As the evening progressed, and the ukulele notes faded into songs from the Bluetooth speaker, we began taking turns as the DJ. At one point, I was prodded by shipmates who remembered I had mentioned salsa dancing before and I eventually conceded to their request. I was a little shy at first to break out this side that I hadn’t shown before, but as the music played and I began the steps, my crewmates excitedly jumped into line. As I taught them the quick rhythm and showed them how to coordinate feet and hips, the joy of the movement took over. We were all quickly laughing and smiling as we danced across the swaying deck. The joy of that moment is something I wish I could bottle up and take with me forever.

As scientists, we long for those intimate moments with the natural world where we get to witness its beauty up close and personal. But we would be remiss to ignore the opportunities we get to connect with one another as humans within these scientific settings. It’s in these instances where we can build bridges and forge partnerships that take us to even higher places. In those moments, we transcend the rigidity of our empirical methods and create human connections to the world and people around us which can uncover even greater wisdom than what we would have gleaned from empirical methods alone.

Ala ʻAumoana Kai Uli in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument

Ocean Exploration Trust and partners will conduct a telepresence-enabled expedition to explore unseen deep-sea habitats aboard E/V Nautilus with ROV and seafloor mapping operations in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM) focused on the largely unexplored northwestern section of the Monument.