Aboard E/V Nautilus III: Ocean Flair at Footprint Reef

Guest blog by Marley Parker, Video Engineer

Originally posted by ML Parker Media

Footprint Reef, California | 33.93134, -119.51148 | October 20, 2020

As the ROVs descend through the water column, slivers of silver flash across the monitors. First just a few, then hundreds, then seemingly thousands of anchovies chase our bright lights towards the sea floor. Their presence is the first sign that we are diving in an area abundant with life.

When the ROVs arrive at the bottom 20 minutes later, it appears as though we are sitting in a garden — a really funky garden.

“Welcome to the sponge garden!” Tom says over the Science Party Line channel on our intercom.

Due to COVID19 protocols, our entire science team is shoreside for this expedition. Even though they’re a few hundred miles away and we can’t see their faces, we’ve gotten to know our scientists through their knowledge, insight, and humor. On the 4—8 watch, we’ve enjoyed the company of Tom Laidig and Erica Fruh from the NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

“The 4—8 team is the best,” Tom says around 5am. “Of course it’s easy to get away with saying that when no one else is awake.”

After completing the white balance on the Hercules camera, we begin a transect. Jess Sandoval carefully drives the ROV directly over hundreds and hundreds of sponges. Ben Grassian, our navigator, says, “I feel bad for the grad student who has to review this video and count all of these.”

Jess reports the current is .4 knots. “That’s probably why these sponges are so happy,” she says. “Plenty of food flowing through here.”

“The diversity is incredible.” Tom says. “There are probably 30 different sponges here.”

I ask Tom if this level of abundance and diversity is unique. In his 30 years of working for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Tom says he hasn’t seen many places like this.

“Almost any sponge you could want is here,” he says. “Abi could spend the rest of her career right here.”

He is referring to Abigail Powell, another member of the shoreside science team who works with the NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center, and is generally considered our resident sponge expert.

As we continue the transect, the endless sponges mesmerize us. “This is like a Salvador Dali painting,” Erica says.

Between all the sponges, we spot a variety of other organisms: sea stars, cup corals, and mushroom corals along with several thornyhead fish, long-nosed skates, tiny sculpins, and tanner crabs.

After two hours, we pause at a large boulder covered in sponges. Jess smoothly circumnavigates Hercules around the feature. As she does, the HD camera captures consecutive images which will be used to construct a 3D photo mosaic. Underwater 3D mosaics make excellent outreach tools, but they have important applications in research as well.

“If we come back to this same spot, we can more accurately measure how the feature has changed over time,” Tom says. “See how this one side of the boulder doesn’t have many corals on it? If we come back here in say three to four years, and see corals on this side, that might suggest the currents have changed.”

When we begin our next shift, 12 hours after the start of the dive, the terrain looks completely different. The ROVs are in shallower waters now (150 meters deep) and the seafloor looks as though it’s covered in rubble.

We still spot plenty of sponges though — including a new one.

“What should we call this one?” Erica asks. “Ben, do you have any ideas?”

“I don’t know,” Ben says. “Marley, I need some creative inspiration.”

So many of the sponges remind me of lamp shades from the 70’s. But this one has a bowl shape.

“It looks like a mid-century modern salad bowl,” I say.

The name sticks, and soon we are pointing out “salad bowl” sponges all over the place.

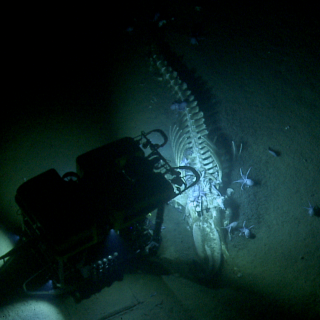

Twenty four hours after putting the ROVs in the water, our third and final shift starts. Once again, the landscape looks completely different, even though the ROVs have only traveled a few kilometers. Right now the view from the Hercules camera shows a field of Acanthogorgia, a mustard yellow hard coral. During a prior shift, Erica was excited to see one of these corals. Now they are everywhere.

“In certain areas of Southern California, you see fields of them like this,” Tom says.

Jess (a native of California) says, “that seems very appropriate for the golden state.”

During the final hour of the dive, Ben and Jess have to navigate around multiple fishing lines strewn across the seafloor. While the rest of us stand by, I reflect on what we’ve seen during the past 24 hours. Out of all the dives from the past month and half, none have boasted as much geological and biological diversity as this place. Between the stunning imagery of the seafloor and the camaraderie of our watch team, I can’t help but feel inspired.

So, in typical fashion, I jot down a quick, silly poem. As the ROVs head back towards the surface, I read it out to the team:

What’s in a sponge, you ask?

Much more than you think!

This is the deep sea after all,

not the kitchen sink.

In an ecosystem diverse as this

options abound — take your pick.

But the fisheries man

Wants to see a trick.

With skill and precision,

Jess positions the ROV.

Using a claw or a hose,

She’ll grab what we need.

To see a myriad of texture

zoom in a bit more.

Then ask a few questions

to the scientists on shore.

Some sponges look like lamp shades,

others clearly hold salad greens

But the most extraordinary traits

are found in their genes.

Thanks to ROVs and research

sponges might offer answers.

Their unique molecular compounds

could help find cures for cancer.

But for now we’re just happy

to visit their habitat.

Rock on righteous sponges—

Corals are old hat.

To see more from the expedition, check out NA123: Channel Islands NMS & Santa Lucia Bank and the E/V Nautilus YouTube Channel.

If you enjoyed this post, read Aboard E/V Nautilus Part I and Part II.

Central California NMS

This joint expedition will visit three distinct areas of Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS), a region comprising one of the world’s most productive and biologically rich ocean areas protecting over 700 species of fish and deep benthic species. Pioneer Canyon is in the northern portion of MBNMS, and is administered by Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary.