Guadalcanal 1942: The Naval Battles That Defined the Pacific War

From August to December 1942, the waters around Guadalcanal became the stage for intense naval engagements that marked a pivotal shift in the Pacific Theater of World War II.

During the Maritime History of Guadalcanal expedition (NA173), the Exploration Vessel Nautilus team will map shipwrecks in Iron Bottom Sound and explore these historic sites through systematic, non-invasive archaeological surveys. The expedition’s focus on combining technological approaches demonstrates new efficiencies in ocean exploration and will examine new sites to determine wreck identity, site extent, and condition.

As the team explores this battlefield, we honor the stories of service and sacrifice made by WWII service members and document these historic shipwrecks in their final resting places on the seafloor as monuments to the consequential naval battles that changed the course of the Pacific.

When people think of World War II (WWII), many picture troops storming the beaches of Normandy or tanks rumbling through Europe. But one of the most significant turning points happened on the other side of the globe—in the dark, churning seas around a tiny island called Guadalcanal.

In the summer of 1942, the Pacific Ocean was a vast expanse of strategic importance, with both the Allied and Imperial Japanese forces vying for control. The island of Guadalcanal, located in the Solomon Islands, emerged as a critical battleground. Here, from August to December, the U.S./Allied and Japanese navies clashed in a series of ferocious, often chaotic nighttime battles for supremacy on the sea and in the air. These were no ordinary sea duels; they were close-quarters brawls, fought at point-blank range with shells, torpedoes, desperate courage, and horrific sacrifice. The stakes? Control of the Pacific Theater of War.

The Strategic Importance of Guadalcanal

Located approximately 1,000 kilometers northeast of Australia, the Solomon Islands is a Western Pacific nation that consists of over 1,000 islands surrounded by 1.6 million square kilometers of ocean. The Solomon Islands were first settled around 30,000 years ago by people from present-day Papua New Guinea, with later waves of migrants arriving from other parts of Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia. After the British settled Australia in 1788, shipping activities through the waters of the Solomon Islands increased significantly, and in 1893, the British colonized the southern Solomon Islands as a protectorate under their control.

A half century later, early during World War II, the Empire of Japan occupied several of the Solomon Islands as part of its rapid expansion across the Western Pacific. To safeguard their strategic operating base at Rabaul, New Britain (Papua New Guinea), the Japanese captured Tulagi in the Nggela Islands in May 1942 and nearby Guadalcanal in June in order to construct a support base and airfield.

Supply lines and resource priorities were stretched thin as war spread across the Pacific, eastern Asia, and Europe. However, the urgency on the Pacific front escalated for the Allies as it became clear that the completion and control of the airfield on Guadalcanal would offer expanded air operations across the Pacific and command of shipping lanes linking Australia and New Zealand with the broader Pacific. Recognizing this island and airfield’s strategic value, both sides would soon commit substantial naval and air resources to control the island, the airfield, and its surrounding waters.

Setting the Stage

Only eight months after the Pearl Harbor attack, the United States’ 1st Marine Division, supported by naval air and gunnery support, landed largely unopposed on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the eastern Solomons. This was the U.S. Navy's first offensive amphibious operation in the Pacific and the start of a six-month-long seesaw campaign.

With major deployments of Japanese and American forces on the island of Guadalcanal, Japanese naval forces sought to supply troops and to displace American troops from the defense of Henderson Field. As the Allied air unit based on Guadalcanal established air superiority, during daylight hours, Japanese cargo and troop ships were too easily bombed and sunk by American aircraft based on the island, and the difficulty of supplying ground troops increased month by month.

The Japanese forces instead began to focus on airfield attacks and resupply missions via nighttime runs through New Georgia Sound (aka "The Slot"). The eastern end of The Slot in the confined waters offshore of Guadalcanal would become the battlefield of five major naval engagements and would become widely known as Iron Bottom Sound. These fierce night-time naval battles resulted in heavy combined losses of over 20,000 lives, 111 naval vessels, and 1,450 planes, demonstrating the deadly intensity of close-range war, and highlighted evolving naval warfare technologies.

The Naval Engagements: August to December 1942

Battle of Savo Island (8–9 August 1942)

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Imperial Japanese Navy undertook a night surface attack on the ships screening the Allied landing force. The first major naval confrontation occurred near Savo Island, where Allied and Japanese fleets clashed under the cover of night. Japanese cruisers penetrated the Allied defensive perimeter and sank four heavy cruisers in under an hour. There was little coordination among Allied ships, and confusion reigned during the attack. U.S. and Allied naval forces underestimated Japanese night-fighting capability and failed to anticipate successful Japanese counterattacks. The Imperial Japanese Navy had superior night combat training as well as the much more technologically advanced Type 93 "Long Lance" torpedoes.

The Japanese forces achieved a decisive victory while suffering minimal losses themselves. With limited time until daylight to make a second attack, the force did not circle back on the vulnerable Allied transport ships off Guadalcanal, which allowed the battle to continue for the months ahead.

This battle has come to be identified as the worst defeat in a single fleet action suffered by the United States Navy to date. The battle prompted the U.S. Navy to re-evaluate its tactics, leading to improvements in radar use, training, and night combat readiness.

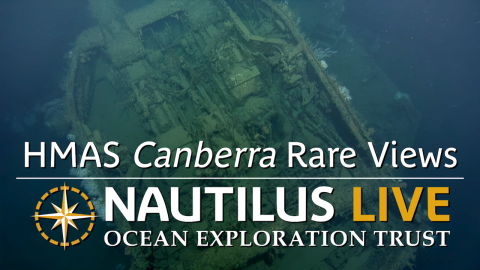

Vessels lost: heavy cruiser USS Astoria, heavy cruiser USS Quincy, heavy cruiser USS Vincennes, and HMAS heavy cruiser Canberra

USS Quincy (CA-39) photographed from a Japanese cruiser during the Battle of Savo Island, off Guadalcanal, 9 August 1942. Quincy, seen here burning and illuminated by Imperial Japanese searchlights, was sunk in this action (NH 50346).

Battle of Cape Esperance (11 October 1942)

Just two months after the disastrous Battle of Savo Island, U.S. forces were better prepared for another night engagement. On the evening of 11 October, the Japanese dispatched a major supply and reinforcement convoy to their ground forces engaged on Guadalcanal. This time, U.S. ships effectively used radar to detect Japanese ships before making visual contact north of Guadalcanal’s Cape Esperance as they approached. This allowed for a preemptive opening bombardment—a major advantage in night warfare. The Japanese were forced to abandon their supply mission. However, the Japanese still landed troops elsewhere on Guadalcanal that night.

Cape Esperance marked one of the first tactical uses of radar in naval combat. It was a preview of how emerging technologies would redefine naval strategy during WWII and beyond.

Vessels lost: IJN heavy cruiser Furutaka, IJN destroyer Fubuki, IJN destroyer Natsugumo, and IJN destroyer Murakumo

First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (13 November 1942)

The multiphase Naval Battle of Guadalcanal consisted of a series of destructive air and sea engagements. The first night of the battle occurred in the early hours of November 13, amid continued Japanese efforts to reinforce their ground units on the island. On a night with no visible moon or stars and interrupted by squalls, this battle most poignantly exemplified the intense and often chaotic nature of naval combat during the campaign, including near misses at high speed and ships firing at point-blank range. In a costly draw with a superior Japanese force, the U.S. Navy lost two admirals and several ships, but stopped the Japanese bombardment of Henderson Field.

Vessels lost: light cruiser USS Atlanta, light cruiser USS Juneau, destroyer USS Cushing, destroyer USS Barton, destroyer USS Laffey, destroyer USS Monssen, IJN destroyer Akatsuki, IJN destroyer Yudachi, and IJN battleship Hiei

Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (14–15 November 1942)

The Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was the decisive conclusion of the brutal multi-night larger battle, and one of the most consequential engagements of WWII in the Pacific. It saw U.S. and Japanese battleships clash at close range, marking a rare surface gunfight between battleships in the modern era. Here, radar-directed firepower altered the course of a battle, proving that radar-equipped ships had a massive advantage in night combat, helping to level the playing field against the Japanese. The Japanese lost multiple destroyers and the battleship Kirishima, and the troop transport and equipment convoy meant to follow the battleships was devastated by U.S. aircraft the next day. After this battle, Japan ceased major efforts to reinforce Guadalcanal with additional personnel, effectively ceding the fight to retake the island and airfield.

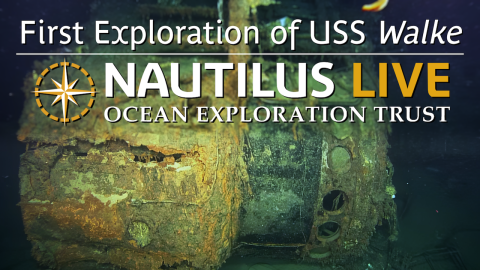

Vessels lost: destroyer USS Preston, destroyer USS Walke, destroyer USS Benham, IJN battleship Kirishima, and IJN destroyer Ayanami

Battle of Tassafaronga (30 November 1942)

In this nighttime engagement, in the waters of Iron Bottom Sound off Tassafaronga Point on Guadalcanal’s northern coast, a U.S. Navy task force attempted to surprise and sink Japanese destroyers dispatched to resupply Japanese ground forces. Despite being a much smaller force, Japanese destroyers launched a successful torpedo attack on Allied cruisers, sinking one and damaging several others. The battle demonstrated the effectiveness of torpedo tactics and the vulnerability of even heavily armed warships. The battle also meant that Japanese transports were unable to complete their resupply mission, with serious consequences for their troops on Guadalcanal.

Vessels lost: heavy cruiser USS Northampton and IJN destroyer Takanami

Learn more about this history in the now declassified combat narrative accounts from the publications branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence.

USS Minneapolis (CA-36) at Tulagi with torpedo damage received in the Battle of Tassafaronga. The photograph was taken on 01 December 1942, as work began to cut away the wreckage of her bow.

Aftermath and Strategic Implications

As the campaign dragged on, conditions for Japanese soldiers ashore grew ever more desperate as supplies of ammunition, medicine, and food became disrupted by U.S. air and sea patrols. Tactics continued to evolve to meet this urgency, including intentionally grounding ships on the shoreline of Guadalcanal to quickly deliver supplies before sunrise and avoid aerial patrols. The success of air coverage from Henderson Field contributed to the large number of vessels lost in shallow water. Starvation and disease were significant contributors to the nearly 35,000 lives lost on the islands throughout the Guadalcanal campaign.

By December 1942, the Allied forces had secured control over Guadalcanal. In February 1943, Japanese forces retreated from the Solomon Islands, marking a major turning point in the war in the Pacific, as Allied Forces transitioned from defensive to offensive operations. Guadalcanal on land, sea, and air was the Allies' first large-scale strategic victory to halt and reverse the Empire of Japan's expansion in the Pacific.

The naval battles not only inflicted heavy losses on both sides but also demonstrated the evolving nature of naval warfare, with important contributions from emerging technology like radar, and where air and surface combat were increasingly intertwined.

Today, the wrecks still lie beneath the waves between Savo Island and Guadalcanal, silent witnesses to a fight that marked a turning point in the war that continues to impact the modern Pacific. The battlefield is on a seabed shallower than 1,400 meters, but lacks high-resolution mapping coverage. To date, only 30 of the military ships lost in this area have been located, with at least 21 remaining to be found in the deep waters of Iron Bottom Sound.

Maritime Archaeology of Guadalcanal: Iron Bottom Sound

Located in the Solomon Islands between the islands of Guadalcanal, Savo, and Nggela, Iron Bottom Sound was the stage of five major naval battles between August and December 1942 which resulted in the loss of over 20,000 lives, 111 naval vessels, and 1,450 planes. These underwater cultural heritage sites now rest on the seafloor offshore Honiara in a confined area less than 25 nautical miles wide, 40 nautical miles long, and 1,400 meters deep.