The Battle of Midway: A Pivotal WWII Engagement within Papahānaumokuākea

During the Ala ʻAumoana Kai Uli expedition, the Exploration Vessel Nautilus will sail to the largely unexplored northwestern corner of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM). While the expedition’s main focus will be to explore the geology and biology of unexplored seamounts, the operating area includes several historically significant shipwrecks associated with the Battle of Midway. As we journey into Papahānaumokuākea and the realm of Pō, a sacred space for Hawaiians, we recognize our expedition area contains a rich and diverse maritime heritage that spans from early Polynesian voyagers who first ventured to this remote region over 1,000 years ago, through, and into the modern era.

As the team maps and explores this region, we honor the stories of service and sacrifice made by Japanese and American service members and document these historic shipwrecks in their final seafloor resting places, monuments of the consequential naval battle that changed the course of World War II in the Pacific.

We uplift the ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) name Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll) to honor the historic and modern connection of the Hawaiian people to the lands and waters now called Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. However, amid military historical documents and popular references, the terms Battle of Midway and Midway may be used throughout this blog for clarity.

History of Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll)

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are the ʻĀina Akua, the sacred elder islands of Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiians). Formed roughly 28 million years ago as a volcano over the Hawaiian hotspot, Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll) has slowly subsided and weathered to a ring-shaped atoll. Located one-third of the way between Honolulu and Tokyo and halfway between North America and Asia, it is home to rich communities of ocean-going wildlife, including millions of seabirds. This shallow atoll, the second most northerly atoll in the world, consists of three islands, coral reefs, lagoons, and shoals.

An aerial view of Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll)

Prior to the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom, the United States took formal possession of the island in 1867. The atollʻs location was considered potentially strategic both for commercial and military planners. By 1903, the first transpacific telegraph cable with a critical station at the island was completed. Throughout the 1930s, Kuaihelani was used as a stopover for Pan-American clipper aircraft crossing the Pacific, the first modern trans-Pacific air transportation route with overnight stops at Honolulu, Midway, Wake, Guam, and Manila.

In 1938, the Army Corps of Engineers dredged the lagoon to deepen the port, and Midway was declared second priority only to Pearl Harbor in terms of naval base development in the Pacific. The construction of the naval air facility at Midway began in 1939, and subsequently, a submarine base was completed in 1942. Ultimately, Sand and Eastern Islands at Midway would feature two airfields and over 5,000 residents. Midway also played an important role during the Cold War (1950s-1970s) as part of the Distant Early Warning line. The U.S. Navy transferred jurisdiction at Midway to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1992.

Airplanes landing at Eastern Island at Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll), 1943.

Kuaihelani in World War II

During the Second World War (WWII), Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll) would become critical to both American and Japanese war strategies.

The Japanese strategy in WWII relied upon the swift expansion of the Japanese Empire into the South Pacific and Southeastern Asia. The strategy also required the establishment of a defensive perimeter of island positions to guard the newly gained territory against attack, consolidate positions, and cut Allied supply lines. In the opening months of the United States’ involvement in WWII, after the attack at Pearl Harbor, Hawaiʻi (December 7, 1941), the Japanese Navy led a succession of raids on islands across the Pacific.

When bombing raids launched from an American aircraft carrier reached the city of Tokyo, and U.S. forces slowed the southward Japanese advance on Port Moresby, New Guinea, the Japanese Naval strategy gained motivation to decisively eliminate the U.S. Navy carrier force. A large offensive was planned to occupy Midway and the Aleutians, thereby securing a defensive line across the Pacific, and drawing the U.S. Pacific Fleet into a decisive battle where it could be ambushed and destroyed. To this end, the Japanese advanced a combined fleet with a carrier strike force including four aircraft carriers — Akagi 赤城, Kaga 加賀 , Hiryū 飛龍, and Sōryū 蒼龍 — and the accompanying Midway invasion task force.

However, weeks before (and unknown to the Japanese), U.S. Navy code-breakersʻ efforts had identified the atoll as the intended invasion target and confirmed the Japanese approach on June 3. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, knowing Midway’s centrality in the enemy’s strategy, resolved to set a trap for the Japanese force by reinforcing the island air base and sending three aircraft carriers — USS Hornet (CV-8), USS Enterprise (CV-6), and USS Yorktown (CV-5) — with their protecting destroyers and cruisers as a strike force to an area of ocean northeast of Midway Atoll.

The Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway began June 4, 1942, and continued over the next three days, with fighting spread across a large expanse of ocean north of the atoll. Squadrons of aircraft attacked and defended Midway Island and searched for and attacked opposing carriers and carrier groups. U.S. and Japanese surface vessels hundreds of miles apart never came close enough to be within sight of one another.

By the end of the battle, four Japanese aircraft carriers and one American carrier were sunk, along with an American destroyer and a Japanese cruiser. Having suffered significant losses and lacking information on the strength of the American carrier force, Japanese strike force leaders made the decision to withdraw from a planned invasion. The Battle of Midway is considered one of the war's most significant battles, as it marked the shift of military power and initiative between Japan and the United States.

Details of the Battle

June 4, 1942

At dawn on June 4, the Japanese launched 108 aircraft from their four carriers ~250 miles northwest of Midway to begin the attack. On approaching the target almost two hours later, US Marine Corps Squadron VMF-211 based at Midway Island, consisting mainly of novice pilots flying obsolete F2A Buffalos and a handful of worn-out F4F Wildcat fighters, rose to meet them. The Americans were quickly brushed aside and scattered with heavy losses by the battle-tested Japanese aviators in modern A6M2 Type Zero naval fighters. The bombing that followed caused extensive damage to the US base infrastructure but left its airfield and runways mostly intact. More crucially, the atoll’s anti-aircraft artillery defenses were still considered formidable and not a single American plane had been caught on the ground, prompting flight leader Lt. Tomonaga to immediately radio back that “there is need for a second attack wave.”

Even as the Japanese First Air Fleet commander Admiral Nagumo pondered this information, lookouts reported US torpedo bombers boring in on his formation. Acting on early warnings from a combination of radio intelligence, reconnaissance, and the newly developed technology of radar, Midway’s defenders had managed to launch all their planes before the air raid commenced. However, a widely disparate mix of units, plane types, and crew training, meant that the American groups arrived piecemeal, diluting their effectiveness. Japanese Combat Air Patrol (CAP) fighters swiftly pounced on the attackers, shooting down all but three of the attacking planes. One of the crashing US bombers passed within feet of Akagi’s bridge before plummeting into the sea, nearly wiping out the flagship’s entire command staff. Orders went out for the Imperial fleet to change the armament of its reserve strike force from anti-ship weapons to land attack ordnance for a second strike on Midway Island.

Fire at seaplane hangar on Sand Island Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll), 1942.

Such rearmament was a laborious process, normally requiring about 90 minutes to complete. Yet only 30 minutes passed when the Admiral received the first scouting report that American carriers had been spotted northeast of Midway. Reversing the previous decision, servicemen hurried to remove bombs intended for land-based targets and rearm the planes with torpedoes and armor-piercing bombs to deal effectively with the enemy vessels now known to be beyond the horizon. However, limited by the number of available ordinance carts and elevators used to handle the bombs and torpedoes, the hangar decks of the IJN carriers steadily filled with stockpiles of dangerous explosives that could not be struck below until after all the new weapons were moved up from their lower deck magazine, assembled, and mounted on the aircraft.

Meanwhile, the American attacks kept coming from the island. US Army B-17 Flying Fortresses rained bombs from high altitude, while below them Marine Corps SBD Dauntlesses and SB2U Vindicators pressed glide bombing attacks, and the submarine USS Nautilus (SS-168) stalked the Japanese ships from beneath the waves. Skillful maneuvering and withering defensive fire from alert escort vessels blunted each of the attack waves. But the necessity for evasive action also came with a growing risk, inexorably separating the Japanese carriers further apart while breaking up the cohesion of their formation. The relentless tempo of combat also hampered the recovery of the Midway attack force. With many of its planes battle-damaged and all running low on fuel, the group had to wait for a lull and land before another offensive operation could begin. Once the last plane was aboard and stowed, the Japanese fleet turned northeast, intent on closing with and engaging what the latest reports indicated was an American aircraft carrier.

Most of the American carrier planes had already been in the air for more than two hours, searching for the Japanese carriers. Once again, a combination of navigational errors, variable visibility, and launching delays led to many of the units becoming separated and strung out, proceeding to the target independently. At approximately 9:25 a.m., the first American carrier aircraft made contact with the Japanese. The Japanese fleet immediately turned away at battle speed, presenting the pursuing planes with a long, grueling “stern chase,” and giving the orbiting CAP fighters an opportunity to swarm in defense.

Unescorted, slow, and lightly armored, the US Torpedo Squadron Eight’s Devastators from USS Hornet were easy prey as they strained to close the gap. One by one, the Devastators fell, followed in succession by two other Devastator squadrons from Enterprise and Yorktown. In the final accounting, 37 out of 41 torpedo Devastators and nearly all of their aircrew were lost without scoring a single hit on an enemy ship.

At this point of the battle, after nearly three and a half hours of combat, the Imperial Japanese Navy had parried every blow the Americans had thrown at them. However, their ships were now scattered, the carriers forced to turn out of the wind to evade repeated enemy torpedo attacks and therefore unable to spot and launch their own strike in response. The defending Japanese fighters had depleted much of their ammunition and been pulled into distant sectors.

Without radar to give early warning, the Japanese fleet was caught completely unaware when the tables suddenly turned. US carrier-based dive bombers from Enterprise and Yorktown arrived on the scene at high altitude, shocking their opponents. These squadrons proceeded to unleash a devastating attack on the Japanese carriers, which were still packed with fully armed and fueled aircraft, as well as scores of unsecured bombs and torpedoes intended for the enemy.

Torpedo Squadron 6 on USS Enterprise

The tide of battle was dramatically and irrevocably changed in the space of just five minutes.

Twenty-eight dive bombers from Enterprise screamed down on Kaga, hitting it with one 1,000-pound bomb and at least three 500-pound bombs. Violent explosions destroyed the bridge, decimating the ship’s command and control team at the moment of extreme crisis. Critical fire suppression systems were destroyed just as volatile aviation gasoline spewed from ruptured fueling lines and ignited. As the resulting flames spread, they detonated an estimated 80,000 pounds of bombs and torpedoes positioned across the hangar deck in a chain reaction series of catastrophic explosions that blew out the sides of the ship’s steel hull.

In the same bombing run that struck Kaga, at the last second, three planes broke off from the formation toward the Japanese flagship Akagi. This three-plane attack landed a 1,000-pound bomb at the aft edge of the middle airplane elevator, penetrating through the flight deck to the upper hangar and detonating in the midst of the fully armed and fueled torpedo bombers being prepared for an airstrike against the American fleet.

The resulting explosion was cataclysmic and led to an uncontrollable fire. Additional damage caused by two near-misses became evident when the ship's rudder jammed 30 degrees to starboard during an evasive maneuver, sending the furiously burning carrier into a circle and rendering it unnavigable. Admiral Nagumo transferred his flag to the light cruiser Nagara to continue the fight. By early afternoon, Akagi was stopped dead in the water, and its crew was evacuated with the exception of the damage-control teams, who remained to wage what would be a losing battle against the spreading fires.

Meanwhile, the Sōryū had been attacked by SBD Dauntless dive bombers from Yorktown and received three direct hits from 1,000-pound bombs along the flight deck. One penetrated deep into the lower hangar deck amidships, while the other two exploded in the upper hangars fore and aft. As with its consorts, the fires on the ship were raging out of control within a very short time. By mid-morning, Sōryū‘s engines stopped and its crew were ordered to abandon the ship as destroyers rushed to rescue the survivors.

In a stunning reversal of fortune, US forces had bombed and critically damaged three of the four opposing Japanese carriers (Sōryū, Akagi, and Kaga). Now only Hiryū remained unscathed and it pulled away from the burning vessels to launch a scratch force of bombers in a desperate counterattack against the American carriers now reported just 90 miles away.

Within an hour, Hiryūʻs fliers discovered Yorktown. Fighting through stiff resistance, the veteran Japanese pilots delivered a punishing attack, landing three direct hits and two near misses on their target. The explosions holed the flight deck and extinguished all but one of the ship’s boilers. As they withdrew, Yorktown was drifting powerless and on fire, incapable of mounting flight operations.

A second strike wave was launched from Hiryū. When they encountered what appeared to be an untouched American task force and turned to attack, unknown to the Japanese aviators, the ship in their sights was none other than USS Yorktown. In the brief interval since the debilitating dive-bombing attack repair teams had restored engine power, doused the fires, and patched the ragged flight deck. When the Japanese returned, Yorktown was making 20 knots, a far cry from the seemingly sinking and burning wreck it had looked to be just an hour earlier. Confident that this was a different US carrier, the IJN strike force bore in on the attack. Despite heavy losses, they hit the already wounded Yorktown, knocking out power once again and taking crucial water pumps offline. The vessel took on an immediate list to port, which quickly increased to a dangerously unstable 23 degrees and the crew was ordered to abandon ship.

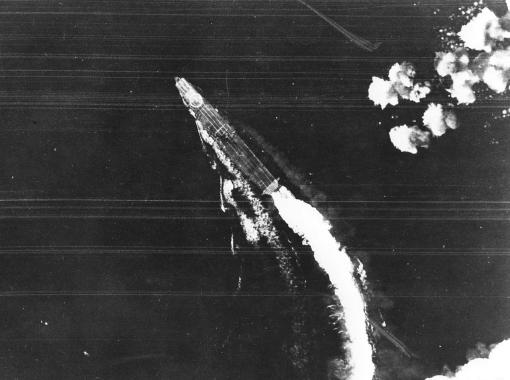

Just out of sight, USS Hornet and USS Enterprise remained unscathed and launched a combined airstrike of Dauntless dive bombers to seek and destroy the last Japanese carrier. Late in the day, the planes located the wildly maneuvering Hiryū and swooped down on the attack. Four 1,000-pound bombs smashed into the flight deck, collapsing it into the hangar below and blasting the entire forward elevator platform from its mounts and where it landed against the ship’s island tower. Although Hiryū's propulsion was not affected, the rushing wind generated by full-speed evasive maneuvers fanned the flames and the fires could not be controlled.

To the south, the rest of the Japanese fleet was similarly unable to contain its fires. The bombing attack and secondary explosions claimed 811 of Kaga's crew. Survivors were evacuated to rescue vessels. Before sundown, the carrier was scuttled by two torpedoes from destroyer Hagikaze to prevent it from falling into enemy hands and sank stern-first. IJN Sōryū was still afloat, but burning violently when destroyer Isokaze was ordered to scuttle the ship with torpedoes. This carrier had lost 711 of its 1,103 crew, the highest mortality percentage of all the Japanese carriers lost at the Battle of Midway, due largely to the devastation wrought in both hangar decks.

After nightfall, Hiryū's engines had stopped and the order to abandon the ship was given. By 3:00 a.m. all the survivors that could be found were moved to nearby destroyers and a torpedo was fired into the stricken carrier to ensure it was scuttled.

The destruction of the Japanese Carrier Strike Force compelled Admiral Yamamoto to abandon his Midway invasion plans, and the Imperial fleet retired westward to regroup. Acting on intelligence that a separate invasion fleet was still in the area, US forces continued on a defensive footing throughout the night.

June 5, 1942

Before sunrise on June 5, as raging fires continued to burn aboard Akagi, destroyers Arashi, Hagikaze, Maikaze, and Nowaki each fired one torpedo into the former flagship, sinking it bow first. 267 of the Akagi's crew were lost.

Within hours of sunrise, Hiryū finally succumbed to its wounds, carrying the bodies of 389 crew members with it to the bottom of the Pacific.

As the US forces pursued the Japanese fleet westward, the damaged Yorktown was reboarded with a salvage crew and the fleet tug USS Vireo (AM-52) took it under tow with hopes of returning the carrier safely to Pearl Harbor.

June 6, 1942

In the early morning hours, after a miscommunication following a canceled mission, two Japanese heavy cruisers, Mikuma and Mogami, collided. Daylight found them slowly moving west and streaming a trail of oil within range of US carrier forces. Dive bombers from Enterprise and Hornet caught up with the stragglers and pounced, sinking the Mikuma with a bomb-hit amidship that detonated its stock of torpedoes. Over 600 of the ship’s crew were lost.

Back on board Yorktown, cutting away loose equipment and dewatering some flooded interior spaces succeeded in reducing the ship’s list. The destroyer USS Hammann (DD-412) came alongside the damaged carrier to transfer personnel and provide additional power and firefighting support. It was at this vulnerable moment when the Japanese submarine I-168 penetrated the protective screen and fired four torpedoes. One struck the Hammann with devastating effect, breaking it in half. Two other torpedoes hit Yorktown below the waterline. Hammann sank in only four minutes, resulting in over 80 deaths.

June 7, 1942

By the morning of June 7, Yorktown capsized and sank, carrying 141 officers and crew to the bottom of the ocean.

Overall, the Battle of Midway claimed the lives of nearly 3,400 sailors and airmen with US losses in excess of 350 and Japanese losses in excess of 3,000. Five major aircraft carriers (Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, and Yorktown), as well two other surface units (heavy cruiser Mikuma and the destroyer USS Hammann), and over 390 aircraft were also destroyed.

Today, this battle is remembered as a turning point where Japanese expansion to the east was halted, and Midway Atoll was preserved and reinforced as an important American outpost. Peace has returned to the atoll, which is now known by its Hawaiian name of Kuaihelani.

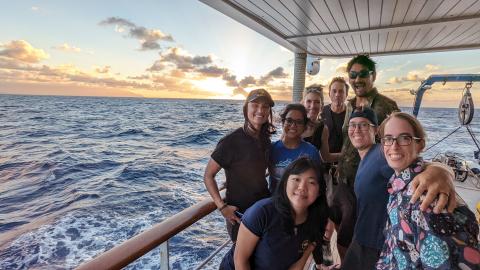

Sunset from Rusty Bucket, Sand Island, Kuaihelani (Midway Atoll)

Recent History and Archaeological Efforts

The analysis and interpretation of this pivotal Battle of Midway have been ongoing for over 80 years. Investigating maritime heritage sites like sunken shipwrecks and aircraft provides unique sources of information. In addition to understanding the event's history, site surveys are critical for resource managers and archaeologists tasked with protecting these underwater cultural heritage properties. And when shared with the public, such site surveys provide vital opportunities for global audiences to honor the stories and keep alive the memory of service, and sacrifice made by servicemen and illustrate the deep history and significance of this area.

Today, the Midway naval battlefield is within the protected waters of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM) — a UNESCO World Heritage site for its cultural and natural significance — which is one of the largest marine protected areas on the planet. Originally established in 2006, PMNM was expanded in 2016 to encompass over 1.5 million square kilometers, including expanding northward to encompass this historic place. A stone monument commemorating the US Battle of Midway National Memorial, erected in 2015, stands on Kuaihelani under the stewardship of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

In 1998, a National Geographic Society expedition led by OET Founder and President Dr. Robert Ballard, and consisting of a team of scientists and US and Japanese Midway veterans, embarked to locate the wreckage of the USS Yorktown. They located and photographed the ship over three miles beneath the ocean’s surface, sitting upright on the seafloor and largely bereft of biological growth.

In 1999, a joint expedition between Nauticos Corp. and the U.S. Naval Oceanographic Office searched this region for the other famed aircraft carriers of the Battle of Midway. Using advanced renavigation techniques and the war-time ship's log of the submarine USS Nautilus, the expedition located a large piece of wreckage, subsequently identified as part of the upper hangar deck of Kaga.

In 2019, Vulcan, Inc. and the US Navy led a multi-week expedition aboard R/V Petrel using autonomous mapping technology and deep-diving robotic vehicles to explore the area. With mapping, the team located IJN Kaga and IJN Akagi and completed a partial visual exploration of IJN Kaga.

Deepwater archaeology comes with significant challenges. The Battle of Midway occurred over extremely deep waters (more than 5,700 meters/18,000 feet/3.5 miles/3000 fathoms). Exploration in this zone is near, for now, the depth rating limits for most underwater vehicles. Despite several previous exploration surveys of the battlefield, the final resting place of the Hiryū, Sōryū, Hammann, Mikuma, and hundreds of aircraft remain unknown.

Today, the sunken ships and aircraft from this historic and devastating battle rest in the darkness of the deep Pacific Ocean. They are archaeological properties in the marine environment, physical records of this significant historic event, and memorials to those lost in the destruction and calamity of a terrible global war. Finally, we can look back as allies and remember this past to shape a more peaceful future together.

Ala ʻAumoana Kai Uli in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument

Ocean Exploration Trust and partners will conduct a telepresence-enabled expedition to explore unseen deep-sea habitats aboard E/V Nautilus with ROV and seafloor mapping operations in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM) focused on the largely unexplored northwestern section of the Monument.