A Springtime Coral Mystery

Spring is in the air here at Nautilus Live Mission Control, where we’re getting ready to kick off our 2014 exploration season in June. To celebrate the budding plant life that surrounds us we’re going to take the opportunity to answer a frequently asked ocean science question - are corals plants or animals?

It’s a good question, considering they are mostly sessile (non-moving) and share their bright color scheme with many land plants. Scientists also talk about corals “taking root,” “branching,” "blooming," and “budding” - all common terms in botany.

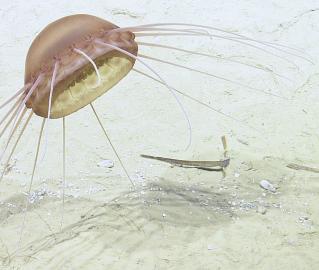

We could tell you the answer straight away, but that’s no fun (if you really can't wait, you can skip down to the end and read the bolded text). Instead, let’s think like a scientist. Here’s the scenario: you are an aspiring naturalist on a diving trip in the Gulf of Mexico, and you’ve just come across a mysterious organism that looks a little something like this:

You recognize it from an old science textbook - that’s definitely a coral. Unfortunately, your memory on the rest of that page is a bit hazy and you can’t remember anything else about the organism. A friend on the trip with you asks - “Woah, is that a plant, or an animal?” You’re stumped, but determined to solve the mystery.

Let’s take a closer look at the question. Before we can figure out what taxonomic category coral falls into we need to establish exactly what makes something a plant and what makes something an animal.

Luckily, your dive boat isn’t too far off shore and you still have cell service. You whip out your handy [insert brand here] smartphone and visit the “Encyclopedia of Life” . A quick bit of research brings you to an incredibly useful page for this particular issue - “What is a plant?”

Time to whip out that notebook - you mark down that plants (in general):

-

are multicellular

-

make their own food through photosynthesis

-

have cellulose-based cell walls

-

are largely stationary

Another bit of searching brings you to the companion page - “Introduction to Animals.” You note that animals (in general):

-

are multicellular

-

rely on other organisms for their food

-

don’t have cell walls

-

are largely mobile

From what you can tell based on your observations, coral are definitely multicellular and appear to be stationary. You didn’t observe them eating anything, and you can’t find a microscope to study their cellular structure. You look up from your phone, turn to your friend and say, “I have a hypothesis. Corals are plants!”

Of course, being a scientist, this cursory level of research isn’t enough for you. You like your initial hypothesis, but want to conduct more tests before you go around making any claims on the status of coral. You reach into your metaphorical science toolbag and consider your options - to experiment or to observe? Experiments are useful in many situations, but you don’t have the time or equipment to set up the very controlled environment necessary for a scientifically valid experiment. It’s settled then - you’ll spend the rest of your sunny afternoon making more detailed observations.

You have another lucky break: your friend finds a small microscope hidden on the boat. With this tool, you have the option of studying the cells of a coral sample. Based on your list of characteristics, you know that if you see cell walls, you have a plant. If you don’t, you have an animal.

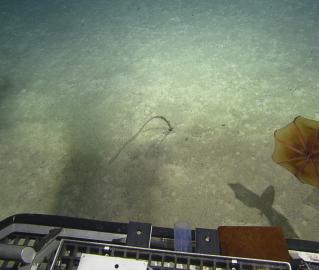

You gear up for another dive, excited to return to the clear blue sea. Down around 10 meters you spot a recently broken piece of coral lying on the seafloor next to a beautiful reef. You grab the piece and swim back to the surface.

Once you return to the boat, your friend has already done the legwork and set up the microscope. You carefully break off a small piece of the dead coral and place it on a slide, then dial the microscope in to reveal the structure - no cell walls! Your hypothesis was definitively wrong - despite outward appearances, corals are certainly animals.

This time, you are right, and you’ve done the research and observation to back it up. You return to shore, proud after a long day’s work. Still curious, you pick up a marine biology textbook and do some more research on corals, learning that:

-

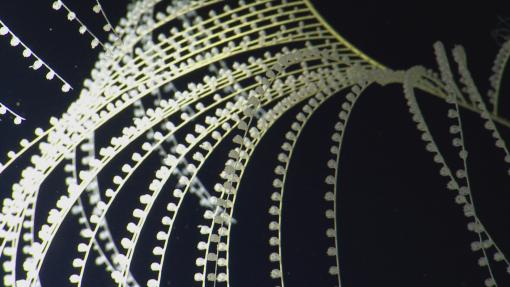

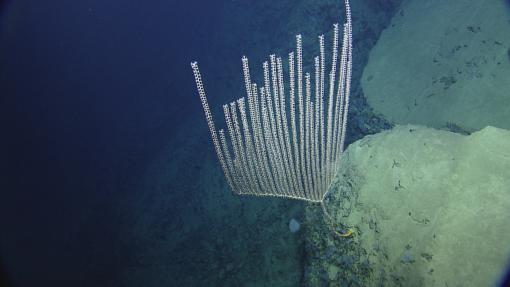

The organism we know as “coral” is actually a colony made up of many genetically identical smaller organisms, called “polyps.”

-

While coral are sessile (that means they don’t move) for most of their lives, many species can use their tentacles to shift position if the need arises.

-

Many of the coral you see near the surface have a symbiotic relationship with a group of photosynthetic algae. The algae provide the coral with energy, and the coral gives the algae a nice home in which to grow.

-

Some coral grows far below where the sun can penetrate. These species are predatory, and capture prey with their stinging tentacles.

-

If you see a particularly large coral, odds are it is old, very old. Scientists have found specimens estimated to have begun life thousands of years ago.

You’ve just traced the path of early biologists, studying the physical appearance of an organism in order to classify it on the tree of life. Scientists now have more precise ways to identify a species - they can genetically sequence an organism to figure out where it fits in the evolutionary history of life. This blog post has already become a bit too long to go into detail, but the genetic sequencing process is fascinating - we’ll make sure to come back to it another week, so keep an eye out.