What are Seamounts?

When we use ROV Hercules to explore the deep sea, we often dive on structures we call seamounts. But what is a seamount, exactly? A seamount is defined as an underwater mountain that rises at least 1,000 meters above the surrounding seafloor. It’s estimated that there are over 100,000 of these submerged mountains globally, most of which are the remnants of extinct volcanoes. In fact, some of the tallest mountains on Earth are underwater. When seamounts are grouped in a chain, we call this a mid-ocean ridge.

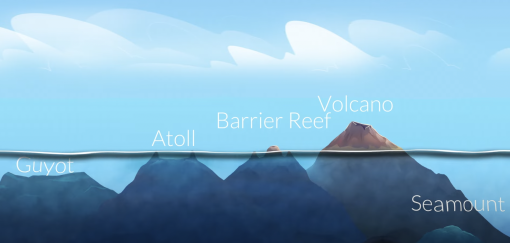

In some cases, seamounts reach above the surface to form a volcanic island. An example of this is Hawai’i’s Big Island, where its still-active volcano, Mauna Kea, is the peak of a massive underwater seamount that rises over 10,000 meters from the seafloor. That’s taller than Mount Everest! However, these islands can become seamounts again if the volcano becomes dormant. Across millions of years, erosion and subsidence may cause the island to sink beneath the ocean’s surface and, in some cases, form a special kind of flat-topped seamount called a guyot.

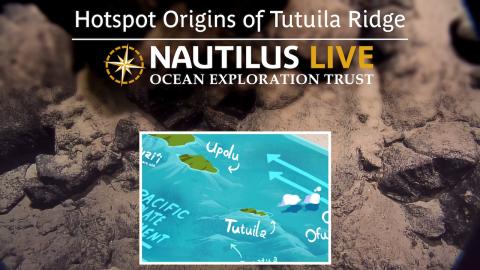

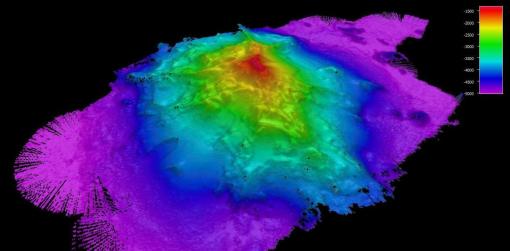

Mapping and exploring an underwater mountain range can tell you a lot about the tectonic plate underneath. Hotspot volcanos form at thin places in the crust — hotspots — where molten hot magma from the mantle is piped upward through the earth’s crust and hits the ocean water, forming ever-growing mountains of solidified lava. Over millions of years, as tectonic plates drift across a hotspot, the process starts again, creating a series of seamounts and islands known as a chain, with the youngest closest to the hotspot and the oldest farthest away.

The trend — or connect-the-dots direction — of a seamount chain matches the movement direction of the tectonic plate below. The Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain is an excellent example of this process. As the tectonic plate moves northwest, active volcanism creates a seamount chain and - in some cases like Hawai’i - islands that eventually erode and subside into underwater seamounts over millennia.

Understanding seafloor structure is made possible through seafloor mapping with the multibeam sonar and sub-bottom profiler systems, which are mounted on the hull of E/V Nautilus. These sensors provide essential insight into the seafloor's features, such as height, location, shape, and reflective nature. Scientists use that information to determine the best locations for future exploration with ROV dives.

There are so many hotspots and seamounts (an estimated 50,000 in the Pacific basin alone) that it can be hard to trace their geologic history. Collecting rocks from the seafloor and analyzing them in a research lab can tell us how and when they formed and if they relate to nearby seamounts. Once ROVs are on the seafloor, explorers look for in-situ rock samples and unique locations to take sediment core samples, which help researchers better understand the seafloor's composition, formation, and age.

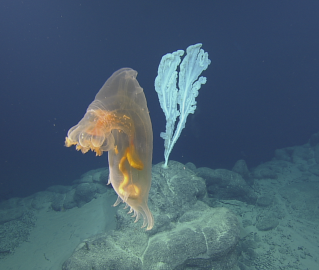

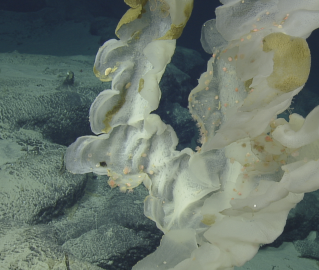

Seamounts and the rocks found on them are particularly important for hosting deep-sea or cold-water coral and sponge communities, which often provide nooks for fish nursery grounds and homes for other benthic organisms. From base to peak, seamounts offer important structure for life to form across different ocean zones, supporting the astonishing biodiversity we encounter while exploring the deep sea. Annually, humans fish more than 3 million tons of seafood off seamounts, with many of these sites outside management jurisdiction for sustainable catch.

Seamounts also play an important role in ocean circulation. As cold salty water bodies flow along the seafloor, seamounts block their paths, forcing the water to accelerate upward. This upwelling mixes waters with different salinities and temperatures, concentrating nutrient-rich waters toward the surface. Upwelling increases the productivity, or amount of food grown, in these areas full of life, like drift-feeding corals, making nurseries for large schools of fish, which can then create food supply up to the surface for sea birds, whales, and larger fish.

The Ocean Exploration Trust is proud to have been exploring the ocean- and its seamounts- for 15 years, seeking out new discoveries in the fields of geology, biology, maritime history, archaeology, and chemistry while pushing the boundaries of education, outreach, and technological innovation.