USS Independence: A First Look After 65 Years

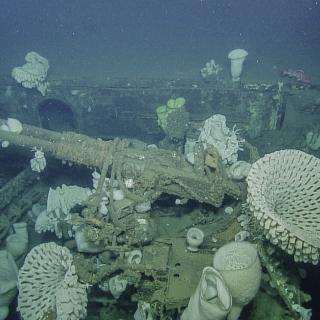

In March of 2015, scientists from NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS), Ocean Exploration and Research (OER), and the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) positively identified a target believed to be USS Independence 30 miles off San Francisco during an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) survey. The aircraft carrier was the first vessel constructed during the middle of World War II as an adaptation of a Cleveland class cruiser hull turned into a fast carrier. Constructed in New Jersey in 1943, Independence reached Pearl Harbor in July of 1943. She was involved in numerous battles in the final two years of the war, including her planes’ attack on and sinking of the Japanese battleship Musashi during the battle for the Philippines.

After the war, Independence was one of two aircraft carriers to be positioned at Bikini Atoll for the Operation Crossroads nuclear bomb tests. Two plutonium implosion-type “Fat Boy” bombs were detonated on July 1 and 25, 1946, damaging and irradiating Independence but not sinking her. The ship was towed back to San Francisco and underwent decontamination testing before being scuttled by the Navy off the coast in 1951.

Prior to the 2015 survey, the Maritime Heritage Program at ONMS investigated the risks of radiation levels at both the shipwrecks at Bikini Atoll as well as what would be expected on the Independence site. Initial readings of radiation are reported to have declined dramatically between the original readings on the ship after the detonations and when readings were again taken after the transit to San Francisco. Further decontamination by acid and sandblasting was conducted during the years in San Francisco following this. Radioactive waste, including the cleaning materials from these decontamination efforts, was sealed in concrete in metal drums and stored in part of the ship for the sinking.

The Nautilus mission to visit Independence this summer carefully considered the potential radiation and contamination risks posed by the site prior to undergoing this expedition. Several factors, including the following, indicate that the risk of contamination should be low. First, many radioisotopes produced by the bomb will have already decayed away. Even cesium and strontium, with 30-year half-lives, are mostly gone after 70 years. Second, any contamination dissolving into the seawater will likely have been significantly diluted in the ocean, and is expected to be much less than the naturally-occurring radioactivity present throughout our environment in the form of potassium, uranium, and thorium. Also, the radiation emitted by the radioisotopes tends to travel no more than a few inches, due to the density of water.

In 1989-1990, the Submerged Resources Center of the National Park Service sent a team that included Dr. James Delgado to archaeologically document and map through scuba surveys several of the Crossroads wrecks at Bikini. Prior to these surveys, Dr. William Robinson of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory wrote that “the potential dose to a person swimming in the Bikini lagoon in and around the sunken ships is so low from both the activation products originally induced in the ships and from radionuclides in the sediment that it can essentially be considered zero.” Today, Independence rests half the Pacific Ocean away from those nuclear test areas, and so the risk in the water is expected to be even lower.

Finally, the safety of the ROV and its samples will be confirmed through immediate on-site radiation measurements performed by the Berkeley Radwatch group, headed by Professor Kai Vetter. Small samples of sea life in the vicinity of the ship will also be collected by the ROV and brought to U.C. Berkeley for sensitive gamma-ray measurements to analyze any man-made contamination.

Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary

Nautilus will return northward along the California coastline for a cruise to study the cultural heritage and natural wildlife in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary (GFNMS). Recently expanded to protect 3,295 square miles, GFNMS contains over 400 shipwrecks and is largely unexplored in the deepest portions.