What Happens to Collected Samples?

The moment a dive wraps up, the science team onboard anxiously awaits the opportunity to collect their samples from the ROV to start processing them in the ship's Wet Lab. After all the samples are collected from the various compartments and collection devices on Hercules, the lab becomes a busy place with scientists, students, and interns analyzing, processing, and packing the many samples collected during the dive.

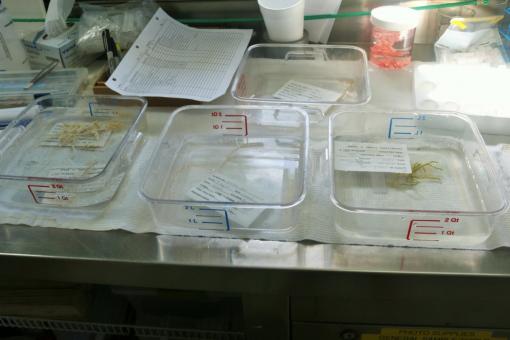

Attention to detail is paramount during sample processing. Each sample is assigned a number when it is collected so that scientists can keep careful track of individual samples throughout their scientific analyses. The sample numbers also allow us to correlate the samples with the metadata (e.g., depth, temperature, and precise location) at which they were collected.

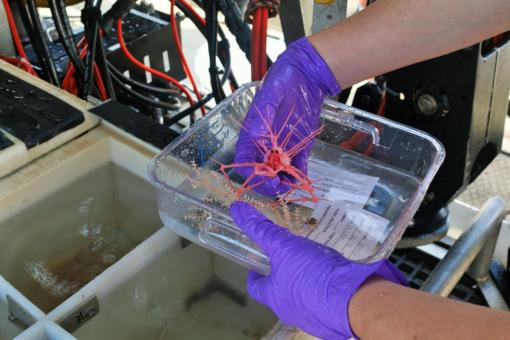

With such a small percentage of our oceans explored, odds are in our favor that we'll find new species semi-regularly. Amanda Demopoulos, one of the lead scientist during the Anegada Passage leg of the 2014 Nautilus Expedition, claims that her favorite sample on the cruise was the Neolithodes sp. (known onboard as "the pink spiky crab"). Why? Because it was a challenge to catch, but worth the extra effort since it is very possibly a new species known to scientists.

The team huddles around a particular sample, fascinated. Note the rubber gloves - any bit of oil or dirt from a human hand could contaminate the sensitive samples. The rubber gloves don't just protect the samples, they also protect our scientists from stingy bits, sharp bits, etc. Some of the sponges, like the glass sponge, have sharp glass fibers inside. If these are handled with bare hands, they could result in some nasty glass splinters.

In addition to labeling each sample, they are also noted in the wetlab log so we have a record of what processing was done, some basic characteristics of the sample, and where it needs to go once the cruise wraps up. Each sample is stored in a solution called RNAEventually, which preserves the RNA present in living tissue. This allows scientists back on shore to study the genetic makeup of all of our samples without worrying about deterioration.

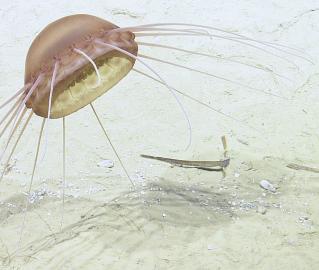

Each and every sample is photographed - we amass quite a library of these photos by the end of each cruise. These samples are matched up with photos of the specimen underwater so we know what it looks like in its natural habitat.

One of the coolest tools in the wetlab has to be the rock saw. Even though we didn't use it during this cruise leg, this saw is capable of cutting open rocks with a clean cut, instead of having to take a hammer to it. Nicole Raineault, the expedition leader, said, "my favorite part about the wetlab is our ability to use the rock saw. Because most of the rocks come up looking the same, this allows us to cut a straight line into the rock to see what kind it is".

Once the cruise wraps up, our samples will be offloaded and sent to labs for analysis. Because samples are typically stored in multiple ways (alcohol, formalin, drying, or RNAeventually), it is possible for interested scientists to look at both the morphology and the genetics of each sample. We need both of these types of information to know if it is a member of a previously known species or if it is a brand new discovery!

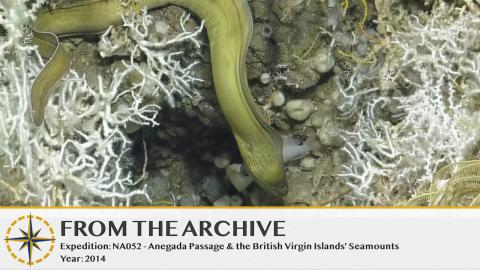

Anegada Passage & the British Virgin Islands' Seamounts

Within the Caribbean region, numerous unexplored seamounts punctuate the seafloor holding records of geologic, biologic and oceanographic processes over different time-scales. Seamounts are topographically and oceanographically complex with environmental characteristics that vary greatly and have often been suggested to be biodiversity hotspots, however, many of these hypotheses are only beginning to be explored in detail.