Nautilus Discovers New Nematode Species

Here’s a popular question from Nautilus Live viewers - what happens when we find a new species?

The answer is more complicated than you’d think. There are millions and millions of species in the ocean, and scientists estimate that we’ve identified fewer than 10% of them. Many of those species are microscopic - we could fly past them all day with Hercules and never notice.

Sometimes; however, we get lucky.

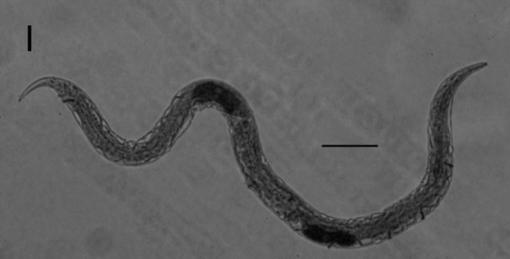

Two members of our Corps of Exploration published a journal article last month confirming that, in 2011, we discovered a never before seen species of nematode - Halaphanolaimus sergeevae. It’s named after Professor Nelli G. Sergeeva from Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas (IBSS), Ukraine.

The authors both sailed on Nautilus during that expedition - Derya Ürkmez from department of Hydrobiology at the Sinop University Department of Fisheries in Turkey, and Mike Brennan from the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island

It was during our 2011 coastal exploration of the Black Sea that we found the new species. You might remember that leg for other reasons - it produced some of our most memorable shipwreck footage, including the discoveries of Eregli C and Sinop H.

When we weren’t looking at shipwrecks, we were taking push-core samples to study differences between the oxic and suboxic layers of the Black Sea. We found the highest density of nematodes in the suboxic layer, but it was in the oxic layer that we found the first ever recorded sample of Halaphanolaimus sergeevae.

The Black Sea is a particularly interesting body of water - on the surface is the oxic layer (approximately 0m - 50m) with a high level of dissolved oxygen. In the deep waters (approximately 100m - 2000m) there is almost no dissolved oxygen at all (leading to a lack of sea life and some very well preserved shipwrecks). This anoxic zone is full of hydrogen sulfide, harkening back to the composition of the primordial seas from which life first arose. In the middle of these two zones (approximately 50m - 100m) is the suboxic zone, with low concentrations of both dissolved oxygen and hydrogen sulfide.

How did we know Halaphanolaimus sergeevae was a new species? On first glance, it looks like a type of nematode discovered in 1914, Halaphanolaimus pellucidus. When our team put it under the microscope for closer inspection, they noted that it had a few defining characteristics to separate it from other members of the genus Halaphanolaimus. That includes a smaller body size, longer spicules (these are tiny, spike-shaped structures), a different location of the amphid (sense organ), and a smaller tail/spicule ratio - amongst other things.

So that’s it, right? It’s not quite that easy - you may have noticed that we’re just talking about this now, even though we collected the specimens over two years ago. The laboratory process is very time consuming. Once the specimen is separated from the surrounding sediment scientists will carefully note and log its physical characteristics, then compare them to those of every other similar species to ensure that it is indeed a new discovery. Once this lengthy process is complete (and it’s especially difficult with Nematodes, considering their diversity) the results are written up into a journal article and checked by several other established scientists to ensure that the final report is accurate.

A lot of what we do here on Nautilus Live focuses on the data gathering part of science - we sail, we explore, we collect data and samples, and viewers around the world can tune in live and participate. Even though we don’t broadcast it, the science doesn’t end when our ship gets back to port. All of those samples need to be catalogued, analyzed, and published with the existing body of knowledge on a particular subject.

It’s not quite as glamorous as the exploration and data gathering side, but it’s where the meat of the science happens - it means that our data gets processed and added to the total body of human knowledge. Sometime it’s a map of the ocean floor, sometimes it’s rock compositiond data, and sometimes, like with our Nematode, it’s a brand new species added to the catalog of life on Earth.

The full journal article isn’t available to the public, but if you or your institution has a subscription to Zootaxa you can access it and read more about Halaphanolaimus sergeevae and the exact methodology by which it was identified as a new species here: http://biotaxa.org/Zootaxa/article/view/zootaxa.3691.2.2

---

Ten Things You Probably Didn't Know About Nematodes:

-

There are over 26,000 known species of nematodes (also known as roundworms).

-

Scientists estimate that there may be over 1 million individual species.

-

They are found in every environment on earth, from polar ice caps to deep ocean trenches to your own back yard.

-

They make up 80% of all individual animals on Earth.

-

They are small - between 0.1mm and 2.5mm in length.

-

They are numerous - you can find over 1 million individuals per square meter.

-

One species, C. elegans, is particularly famous - it was the first organism to have its genome sequenced.

-

They are found as parasites in most living species - including humans.

-

It was the only living species to to survive the Columbia shuttle disaster.

-

They can undergo cryptobiosis - that means they can freeze and return to life right where they left off.

Internal Wave Motion of the Southern Black Sea

Expedition NA012 in the Black Sea explored the transitional zone between the oxic and anoxic water layers along the paleoshoreline at ∼155 m depth. This expedition conducted comprehensive side-scan sonar survey grids at depths from 100- 400 m off Eregli and Sinop, Turkey to document acoustic changes in sediments across the oxic/anoxic boundary.